When you are faced with a no-win scenario, there are only two ways to avoid losing: refusing to play or changing the rules.

Realizing they are losing the battle for (their kind of) America, Republicans — perhaps mindful of what transpired 150 years ago — have begun organizing themselves around door number two, changing the Constitution.

More precisely, changing it back.

The first constitution, the Articles of Confederation (AoC), first drafted around the same time Thomas Jefferson penned The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, had everything a 21st century Republican could wish for: a powerless Congress — it couldn’t even tax and needed a 9/13 majority to pass any law — no Supreme Court with the power to invalidate state laws and no executive branch to enforce acts of Congress. In short, a federal government that really was small enough to drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub, as Grover Norquist once famously said.

It was also hopelessly ineffective, though. Article II of the AoC read: “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” What the Articles of Confederation created, therefore, was a United States in name only, a “firm league of friendship” (as the Articles called it) between thirteen independent, sovereign countries.

Of course when the Articles were ratified, in 1781, the Thirteen Colonies were still fighting for their independence from the British Empire, and it was perfectly understandable they had no desire exchanging one meddling, central government that was forcing all kinds of ridiculous taxes down their throat for another.

But understandable or not, founding the United States on the principle of sovereignty for individual member states also proved highly impractical. It led to frequent disputes between the states, foreign policy conundrums — because some states entered into agreements with non-U.S. states on their own — a weak military and unstable state economies, because each member state printed its own money and competed with the others when trading with the European powers.

The original mission of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 — to revise the Articles of Constitution — was doomed to fail, because the first constitution was founded on a logical fallacy: shared sovereignty.1 The solution was to either stop pretending and abandon the concept of the ‘United’ States altogether, or to double down on it and create a strong central government, with the supreme legislative power — including the power to tax — vested in Congress, the executive power in a President and the judicial power in a Supreme Court.

The new Constitution thus decided the fundamental disagreement about the nation’s political organization between the so-called Federalists and Anti-Federalists, in favor of the former, though tension between the two sides remains to this day.

Having said that, no sensible Republican (i.e., Anti-Federalist) would want to replace the current Constitution with the Articles of Confederation. Conservatives calling for a new Constitutional Convention want to curb the legislative power of Congress and judicial power of the Supreme Court, not abolish it.

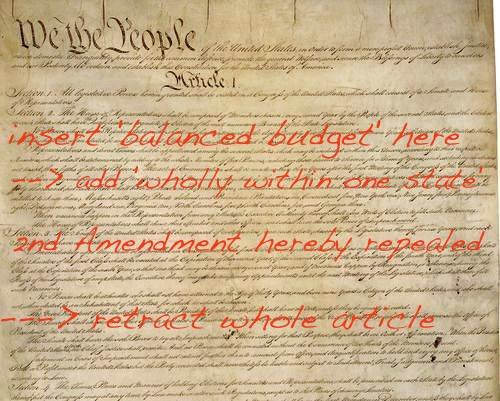

And they have a point, considering that the reason to change the Articles of Constitution at the time, was to strengthen the United States military, economically and organizationally. Is it (still) really necessary, then, that Congress has the power to regulate activity that occurs wholly within one state? Is it so unreasonable to demand that Congress balance the budget? To allow states to decide whether they want to allow abortion, gay marriage, marijuana in their own state? Yes, to most Democrats these are all no-no’s, and to give Republicans salivating over a constitutionally mandated balanced budget and increased states’ rights a quick reality check: none of it will be possible without Democratic support. Here’s why.

Changing the Constitution is notoriously difficult. Article V of the Constitution reads:

“The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress (…)”

These days, having two thirds of both houses agree on the color of a pink elephant would already be historic, let alone getting them to agree on an amendment to the Constitution, so that’s out. Getting two thirds of the states to call for a convention is more feasible for Republicans though, which is why they are concentrating their efforts on this path. Two reasons:

1 — The electoral problem of the Republicans is not that there aren’t enough red states, but that there aren’t enough people living in them. 2 — Article V of the Constitution talks about the “application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states.” (34 of 50 states). Unlike a vote in Congress, which is always a snapshot, the collection of the required 34 applications for a Constitutional Convention may take years. In 2004, Republican President George W. Bush carried 31 states, and several of the states he did not carry — such as Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and New Hampshire — are not solidly Democrat, meaning they could at one point vote to file an application for a Constitutional Convention. Granted, it’s a stretch, but not impossible. As of this writing (January 2016) there are 28 states that have passed applications for a Constitutional Convention to pass a balanced budget amendment.2

But even if Republicans succeed in calling a Constitutional Convention, they would still need the support of the Democrats, as anything coming out of the Convention would only become part of the Constitution “when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states” (38 of 50 states), a number unlikely to be achieved by Republicans on their own.

Democrats could thus in all likelihood block any and all changes to the Constitution. Then again, they could also choose to use that leverage to make some of their own constitutional dreams come true. Repeal the Second Amendment? Constitutionally guaranteed indexing of the minimum wage, universal healthcare, free education? All of which equally abhorrent even to moderate Republicans, but what if they were the price for a constitutionally mandated balanced budget and the right of individual states to abolish gay marriage and abortion?

Would it be worth it?

- See also European Union

- There is considerable debate about whether applications can be rescinded or not -- the Constitution itself is silent on this -- but for the purpose of this article it would go too far to include the various viewpoints on this.